Fraud claims on tenterhooks? The Lord Tenterden’s Act defence

25 April 2022: CYK Partner Jon Felce and Associate Andrew Flynn focus on a legal issue of particular relevance to civil fraud practitioners, as it arose in the recent judgment of the High Court in Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank PJSC v Shetty & Ors [2022] EWHC 529 (Comm). This is the complete defence that the Statute of Frauds (Amendment) Act 1828 (or Lord Tenterden’s Act) may offer to some fraud claims, and the need to consider this possibility carefully at an early stage, especially when giving full and frank disclosure in without notice applications.

Putting together case theories in civil fraud litigation can appear straightforward. While care and attention needs to be given to which cause or causes of action best apply to the particular facts, we all expect to know what a fraud fundamentally looks like: the proposed defendant(s) will have caused loss to the claimant by saying and/or doing something dishonest. Once those core facts are made out, it can be tempting to assume that everything will fall into place and one or more of the usual civil fraud causes of action can be availed of.

However, there are less frequently publicised aspects of the law that can catch the unwary off guard, with potentially severe consequences. The recent judgment of the High Court in Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank PJSC v Shetty & Ors [2022] EWHC 529 (Comm) offers a recent warning in this respect in the context of fraud claims.

The Facts

This judgment concerns applications made in relation to litigation regarding what the claimant describes as “a massive fraud” within the NMC Health group of companies, which had collapsed into administration. Simplifying matters considerably, the claimant alleges that the various defendants were involved in creating false financial statements, which were provided to the claimant to induce it to extend or renew credit to the group. It claims that it would not have lent these sums but for the dishonest statements provided, and has lost some US$1.2 billion as a result. It commenced proceedings in England for deceit and unlawful means conspiracy.

The claimant obtained a worldwide freezing order (“WFO”) at a without notice hearing in December 2020, which it then asked the Court to continue until judgment or further order of the Court. It also obtained permission to serve the proceedings out of the jurisdiction without notice to the defendants. Some of the defendants then applied for both this permission to be set aside and the WFO to be discharged. In arguing both that there was not a serious or real issue to be tried as a jurisdictional matter, and that the WFO should be discharged for the claimant’s breach of its duties of full and frank disclosure, the defendants relied in part on a lesser-known statute that, despite being almost 200 years old, remains good law.

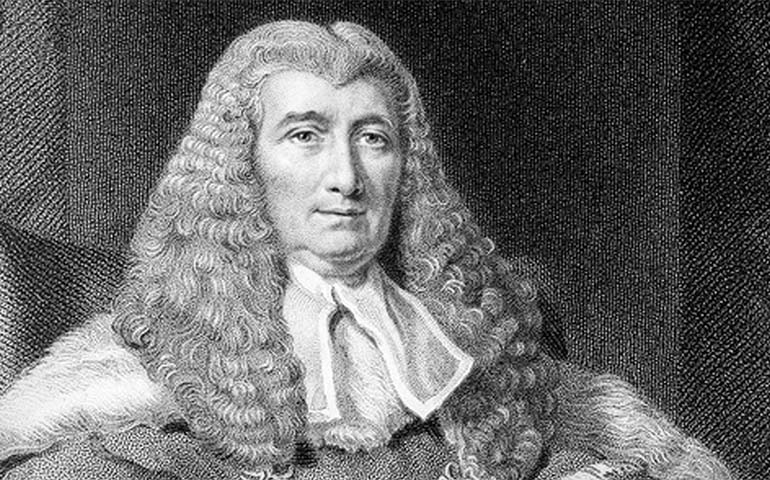

Lord Tenterden’s Act

The statute in question is the Statute of Frauds (Amendment) Act 1828 (sometimes referred to as Lord Tenterden’s Act), and in particular section 6 which bars any action brought on the basis of a representation or assurance regarding another person’s “character, conduct, credit, ability, trade, or dealings” that is made with the “intent or purpose that such other person may obtain [money or goods upon credit]” (as interpreted by the Court of Appeal in Roder UK Ltd v West and another [2011] EWCA Civ 1126), unless that representation or assurance is made in writing and signed by the party against whom the action is being brought. The legislation was designed to prevent actions for misrepresentation arising out of casual oral statements about other people’s financial standing or probity, and thereby avoiding the requirements for guarantees to be in writing and signed as laid down by legislation dating back a further 150 years, namely section 4 of the Statute of Frauds Act 1677.

There are various points of note that arise from the judgment in the Shetty case. The first is that section 6 of the 1828 Act is procedural in effect. Therefore, although there was a dispute in the Shetty case as to the proper law that applied to the claims being advanced, the Judge (HHJ Pelling QC) considered that – by analogy with section 4 of the 1677 Act – section 6 of the 1828 Act would (if it applied) operate as a procedural bar irrespective of the governing law of the claims.

The second point of note is that HHJ Pelling QC resisted the claimant’s arguments that section 6 of the 1828 Act should be construed narrowly, noting that Parliament has retained it and it must be given effect in cases where it applies. He did note that in its modern application it may be confined by case law to fraudulent misrepresentations relating to creditworthiness. However, in concluding there was a serious issue to be tried, he left it as a matter for construction at trial whether it would operate to bar any of the claimant’s claims in relation to implied misrepresentations.

Third, the Judge noted that section 6 may be confined in its application to representations around the creditworthiness of the recipient of any money or goods upon credit, and may not extend to representations concerning related companies of the obligor, as were alleged here. On the other hand, he noted that section 6 arguably cannot be confined to misrepresentation cases only, and could also defeat a cause of action that relied upon a misrepresentation to which section 6 applies (such as unlawful means conspiracy).

A Note of Caution

HHJ Pelling QC ultimately concluded that the onshore courts of Abu Dhabi were a more appropriate forum for the dispute and that the English court therefore would not accept jurisdiction of the claim. In light of this, it was not necessary for him to decide whether the WFO granted in 2020 should be extended.

However, he did make clear that in his view the claimant had been guilty of a material breach of its duty of full and frank disclosure, specifically in relation to the possibility that section 6 may provide a complete defence to the claims. He stated this provision “ought to have been the subject of detailed submission concerning its potential availability as a defence”. As it happens, given the judge’s other findings this point did not benefit the defendants, however had it done so the claimant would have risked having had its WFO discharged and/or faced a heavy adverse costs order.

Conclusion

Given that section 6 is not utilised particularly often, the judgment provides a useful insight into the types of issue that can arise in fraud claims. However, the equivocal nature of some of the comments – which would have required full determination at trial – means that many questions remain unanswered, leaving fraud claimants and defendants alike on tenterhooks.

LinkedIn

LinkedIn Twitter

Twitter Email

Email Print

Print